Last Planet is introduced as a retail solution designed to increase dwell time, reflection and interaction. The project set out to investigate the use of Slow Technology[1] (ST) in a retail environment, this is a point of departure from a study (Boehner et al 2005) where a museum exhibit raised the profiles of the other visitors, leading to emotion in interaction as well as an increase in dwell time. This study pertains to traditional bricks and mortar stores and not online shopping experiences.

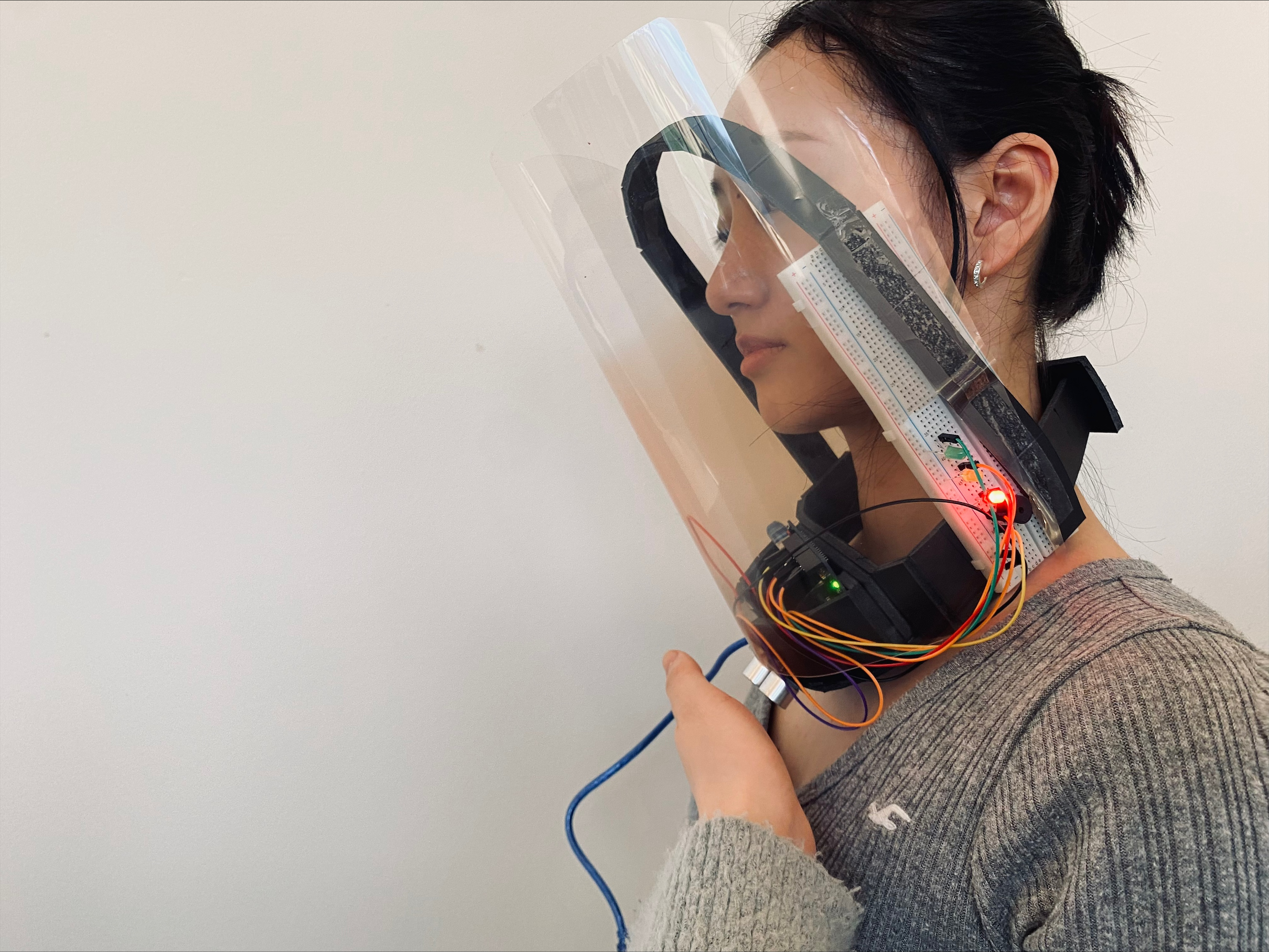

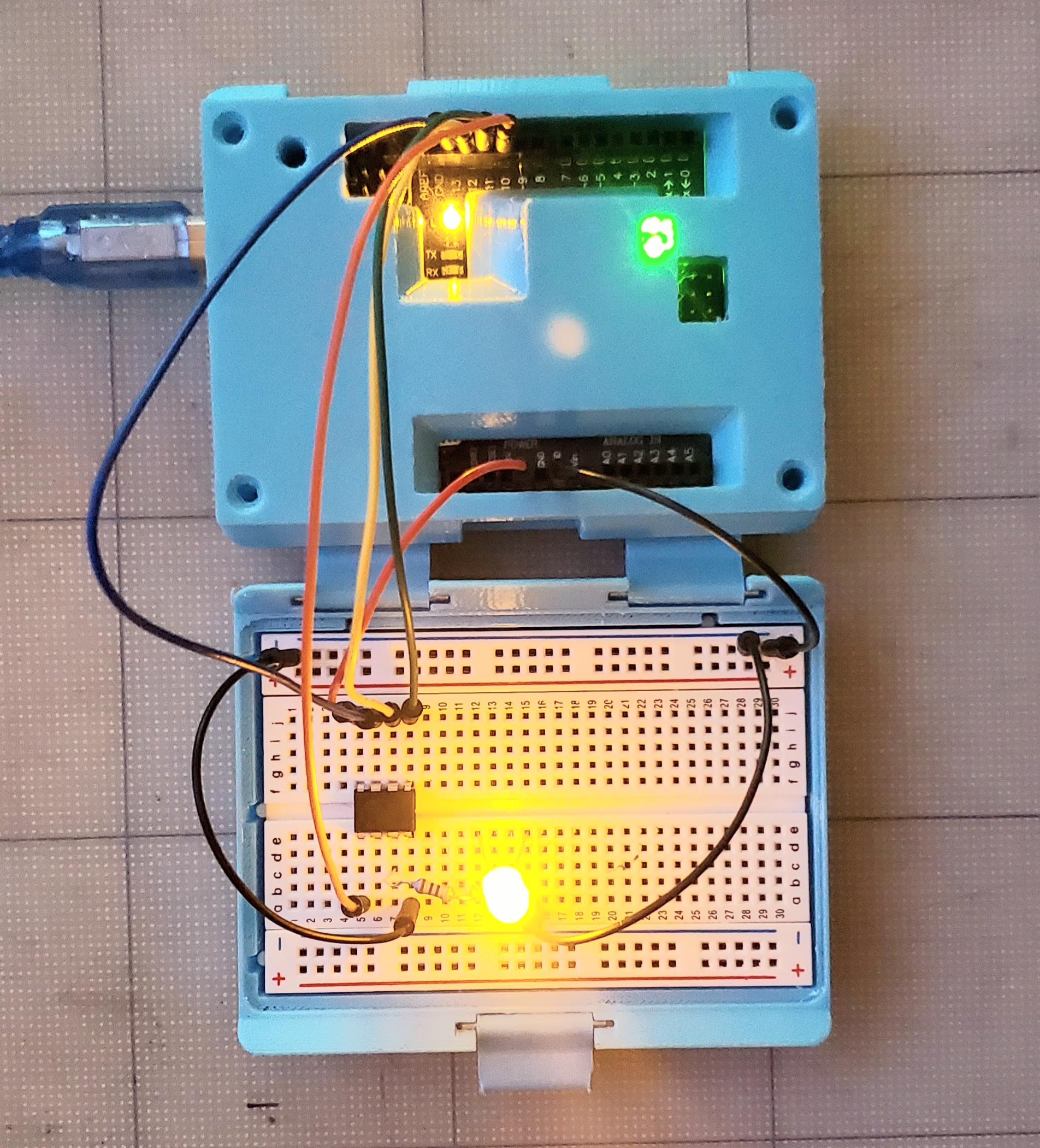

The iPad in the housing for display in a retail environment. Image shows the final solution for this first testing phase.

“…each time they selected an object to learn about, the visitors personally designed imprint was left behind with that object.” (Sengers, et al. 2005)

To test this concept the study examines consumer behavior when there is no device present and the behavior when the device is there, making note of dwell times, engagement, likelihood to return and interaction. Tests showed that people were attracted to the device and interacted with it, many would return to it if they saw it again, indicating that there is founding to integrate Slow Technology in a retail environment. Lastly, ideas for future development will be introduced based on the findings and scope for development.

[1] Hallnäs, L., Redström, J., Slow Technology – Designing for Reflection, Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5(3) 2001.

Introduction

With all our work, our friends and families, the social media we seem to be participating in, the shops seem to be getting bigger and busier, more outlet style places and super malls, we seem to be a busy society in all aspects of our lives with less time and more rush, even having self-check out because we need to check out immediately, and we somehow feel in control of our time if we can check out our items ourselves. It asks the question if the environment can be slowed down, will it enhance our experience? “Slow-Tech” offers an alternative vision for life in the twenty-first century – a rounded vision of balance and robustness that would be healthier for the planet – and healthier for us. (Price 2009)

The constant usage of technology in our lives begins with intentions of closer connections and better productivity, but very often lead to more stress[1] and anxiety that chip away at the overall quality of life. The crux of what (Ferenczi 2011) writes is, “The best interpretation of the Ipsos survey results may be that people feel life is more technologically-infused, complicated and stressful because, well, it is.”

Last Planet focuses on the consumer present in the retail environment, not the products on display, and it offers a chance to catch a glimpse of other consumers present within a certain timeframe. These participants (in this instance) share a shaving tip with their fellow shoppers. The interface also displays to them how often a certain name has been selected, thus raising the profiles to the other consumers. There is also a timestamp when the last planet was created.

It is noted that further investigation could be undertaken to determine optimal location placement of Last Planet as well as scale. These are outside the scope of this project, but environment placement plays an important part “there can be several responses to the environment, responses such as cognitively, emotionally, and physiologically” (Bitner 1992). Last Planet, for example, would perhaps not offer as much reward if it were placed in a quiet low traffic jewelry shop – however the study noted that there was an increase in use of Last planet if the aisle was empty when a solitary person approached it, however, the testing showed it is more popular when a group approaches it.

This study looks at questions of engaging a consumer, capturing their attention and ultimately leading to modified behaviour as these are issues that are examined and continually addressed in the retail environment. The paper will detail what the current thinking is in retail and the current technology solutions used illustrated with examples. It will then focus on a possible solution using ST and how it was implemented in this study.

Taking those essential elements, the project explores if ST, which is seen as reflective and introducing slowness, through materialization or manifestation as well as clear simple design; can we use it in what is traditionally seen as a fast paced heavily market area, fighting for consumers to chose their product.

Has this faced paced society got the time to take time? Can the perceived time be altered so that we have moments of reflection, possibly when we least expect it.

“(slow technology has) longer periods of time associated with dwelling.” (Hallnäs 2001)

Questions

Can a calming and engaging in-store experience, which integrates passive or active user interaction act as a new medium to drive brand awareness/facilitate product placement and influence consumer behaviour and engagement in the retail experience? With the rapid development of retail experiences in the guise of touch screen displays and motion graphics advertising the products down the aisles, would a device which sets out not to bombard the consumer with information, but to give them a space to step back and reflect, be able to capture their attention?

With that in mind, Last Planet will be placed in a retail environment that challenges typical advertising methods. Instead of focusing on selling and describing products it will provide them with information about the people who have been or are still in the shop. Because Last Planet records who was there before them, in the form of their name, a tip they may have left, and the time someone interacted, it has a very different feel to what displays may already be in the shop.

Motivation

Many uses of Slow Technology are artistic[2] in nature, looking to improve the environment. Even those changes to environmental stimuli that are not noticed, or consciously perceived by the consumer, are capable of causing shoppers to change behaviours while inside the store (Turley and Milliman 2000; Milliman 1982).

Last Planet sets out to combine the appearance of an engaging piece and to also provide something that can enhance the environment and interaction for the person using it. This is very much in keeping with the idea that it should in some way enhance the surroundings, which in turn promotes reflection.

There is also an important element of play, “homo ludens as playful creatures promotes engagement in the exploration and production of meaning, providing for curiosity, exploration and reflection as key values. Ludic design focuses on reflection and engagement through the experience of using the designed object.” (Sengers, et al. 2005) that should be implemented to keep consumers interested and engaged.

Hypothesis

This paper sets out to be an investigation of the use of Slow Technology in a retail environment. Can ST be used to capture the attention of the consumer, leading to a more relaxed atmosphere, and increase in dwell time, ultimately increasing their interaction and experience to be more positive?

We should not design for reflection as a stand-alone activity but as one component of a holistic experience, which also includes ongoing activity (Sengers, et al. 2005).

Methodology

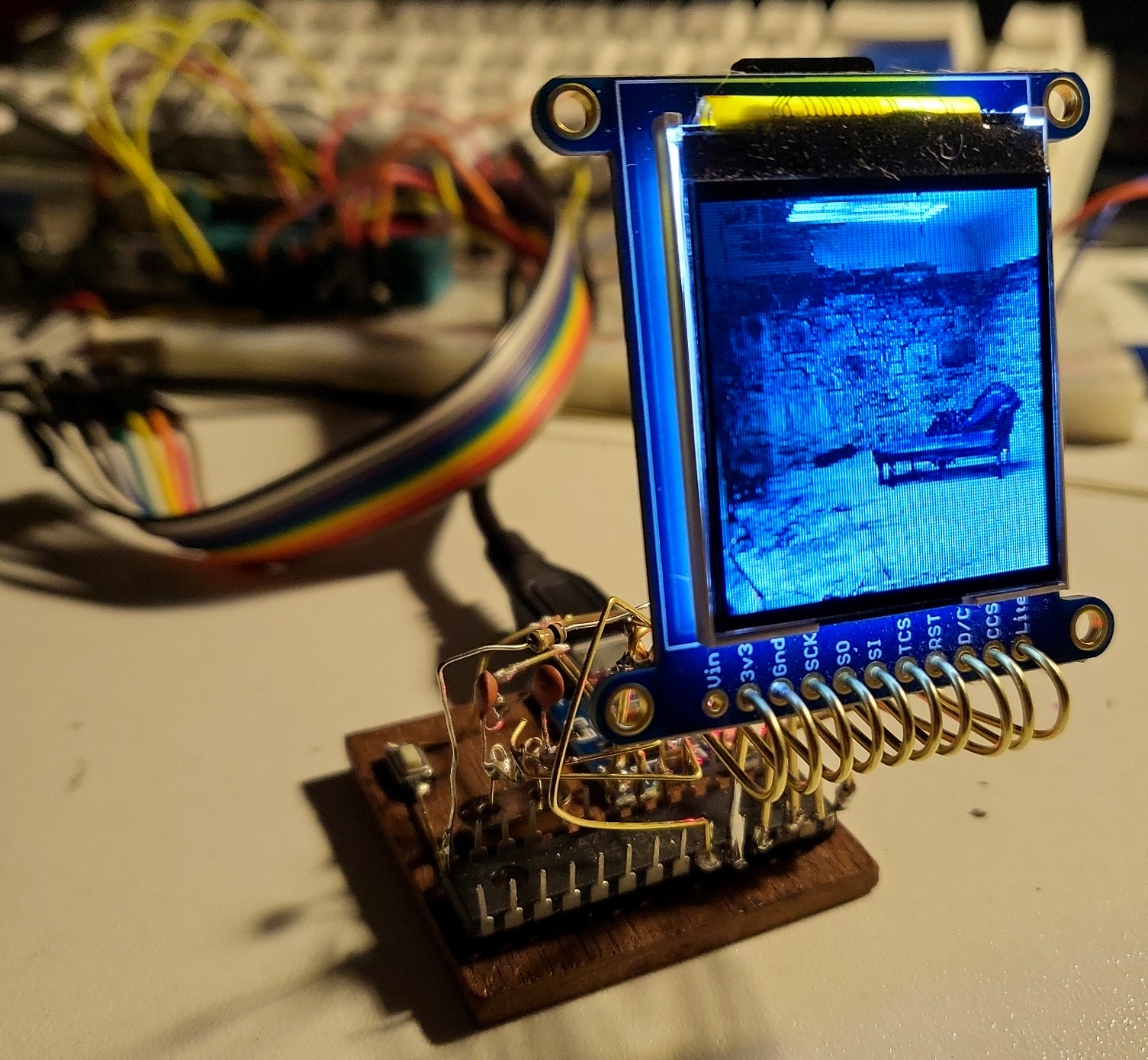

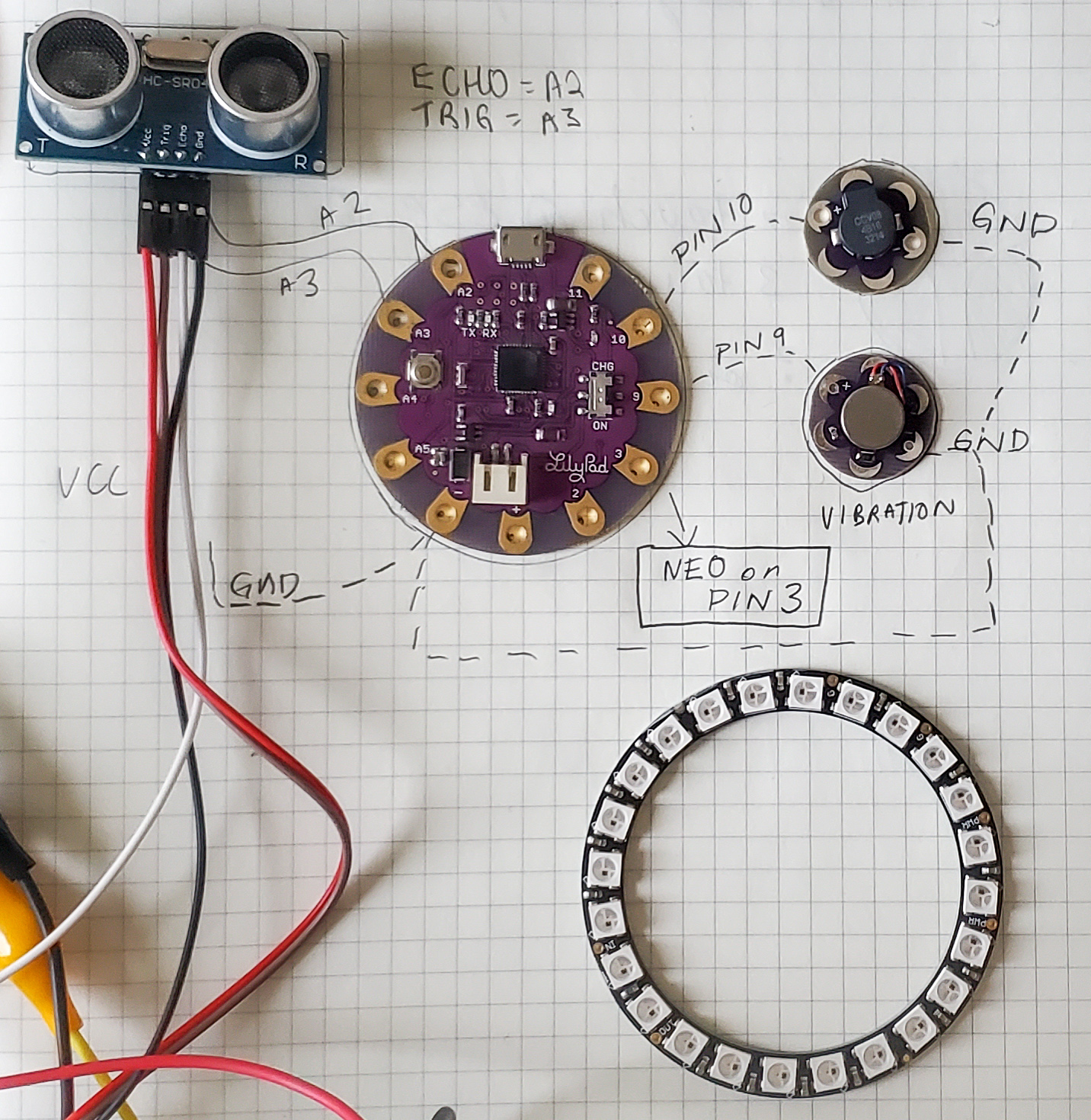

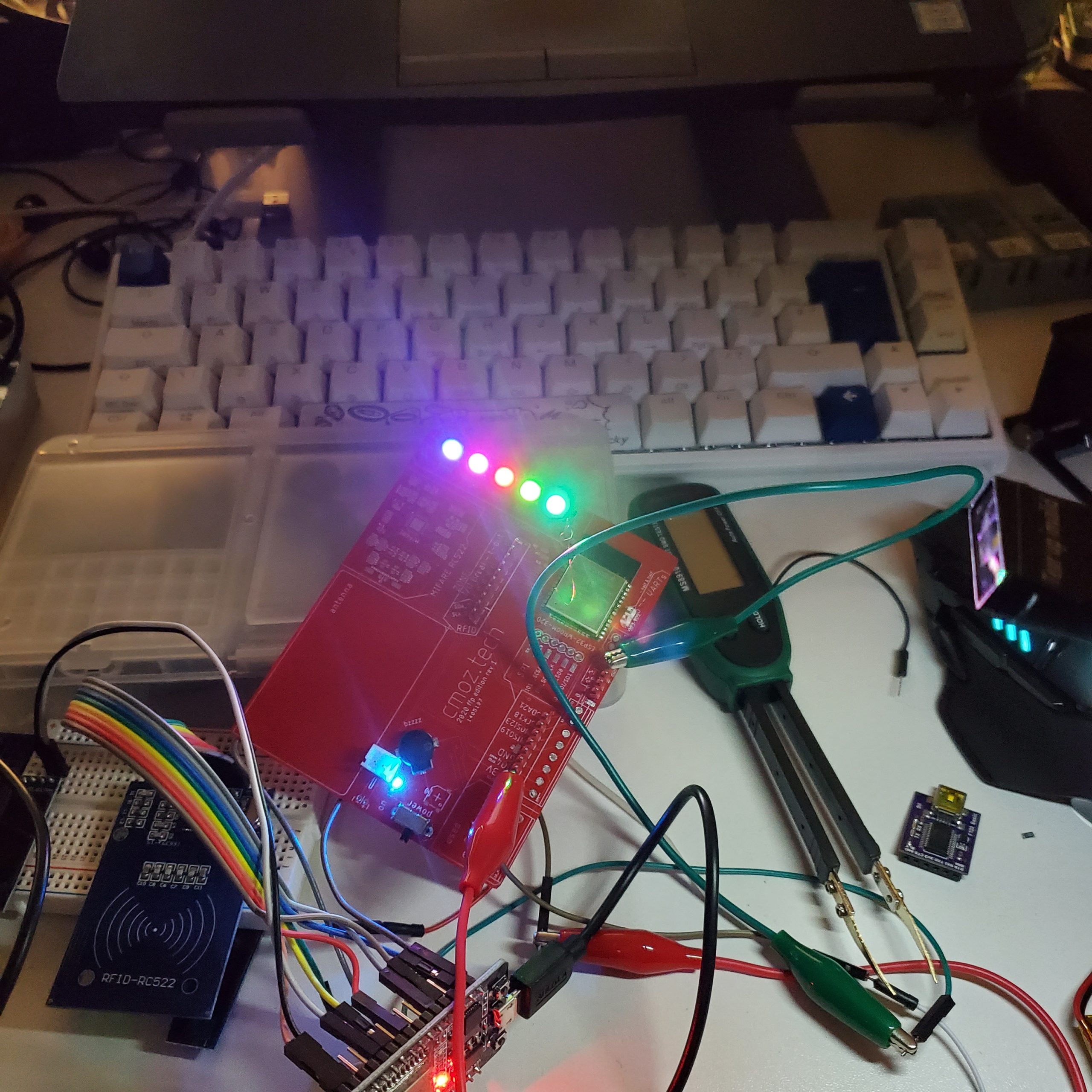

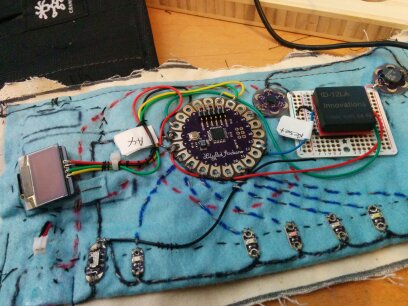

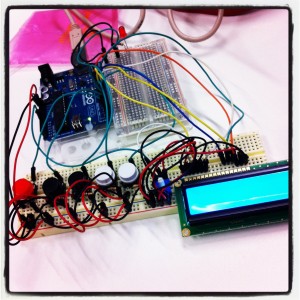

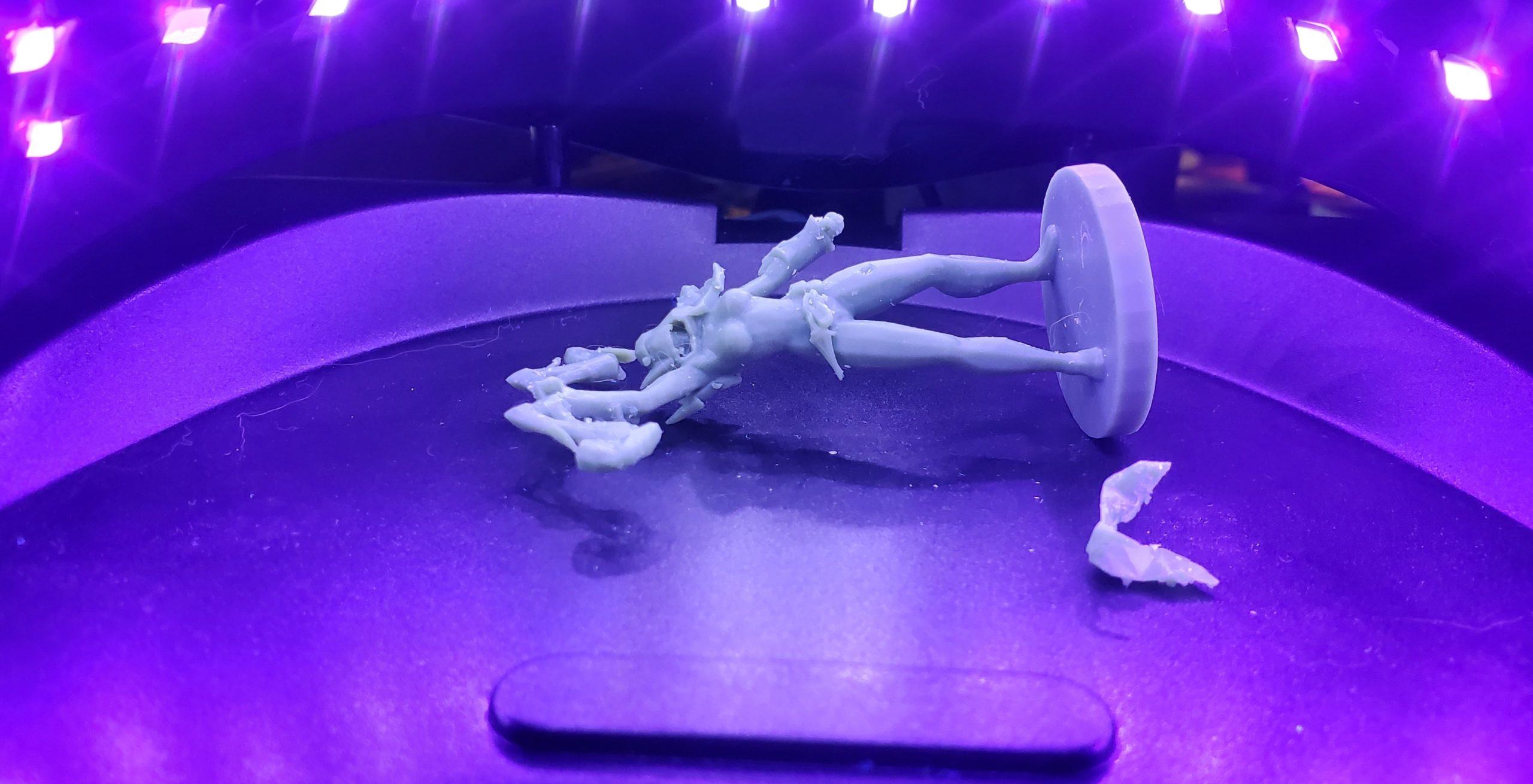

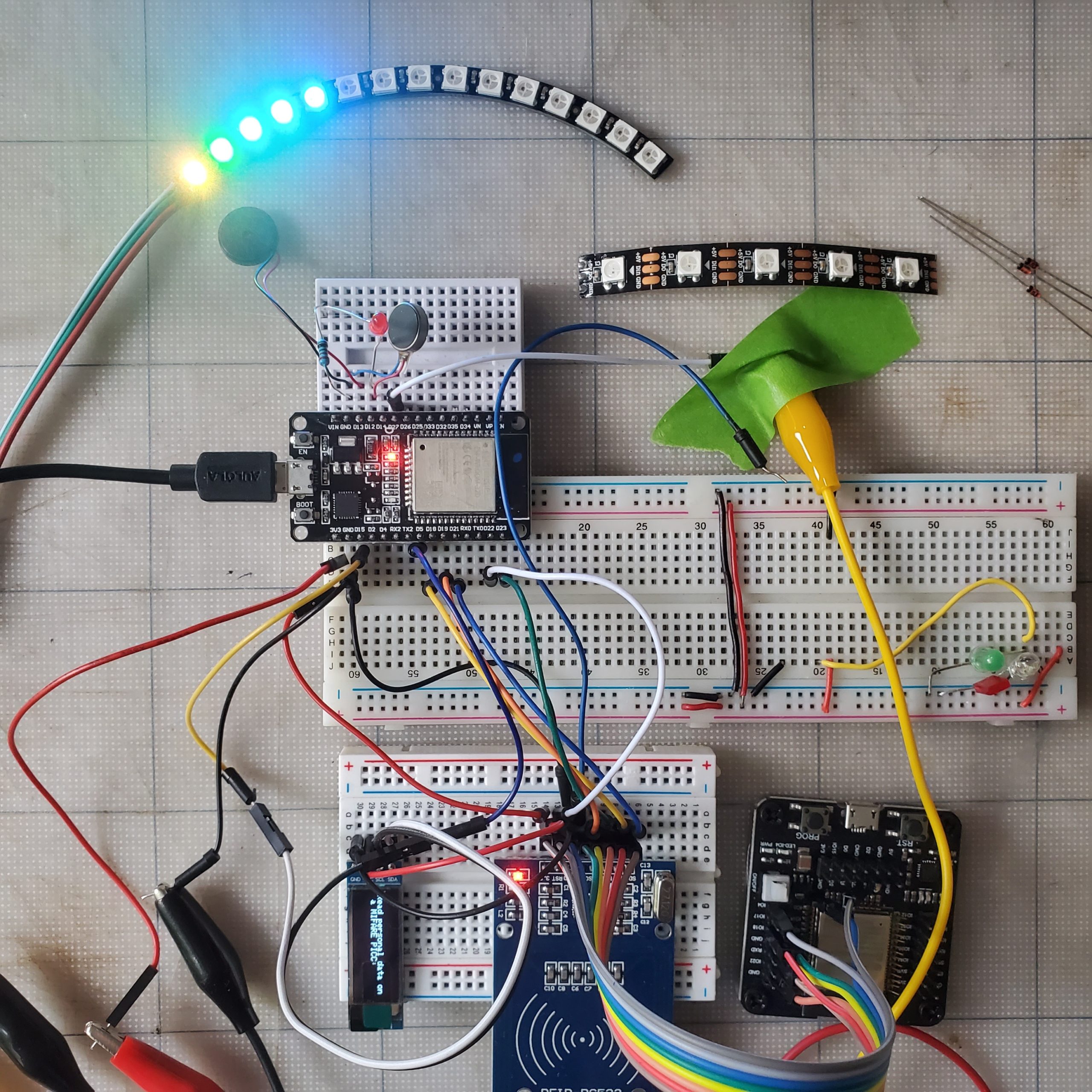

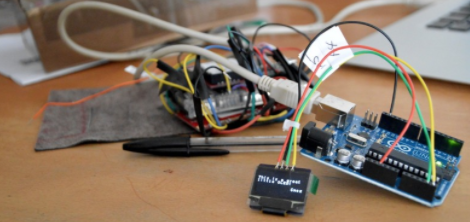

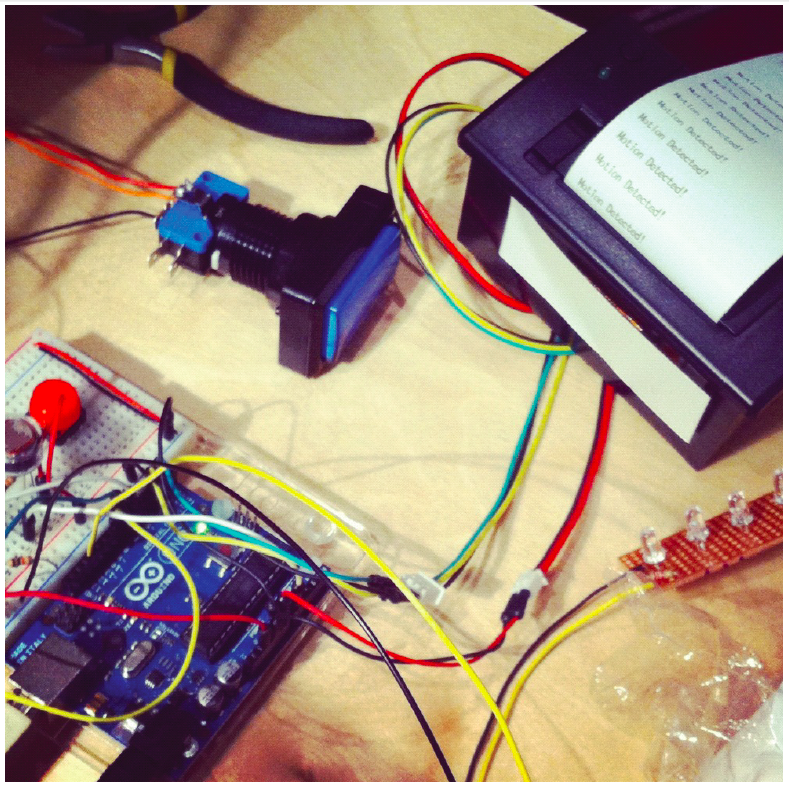

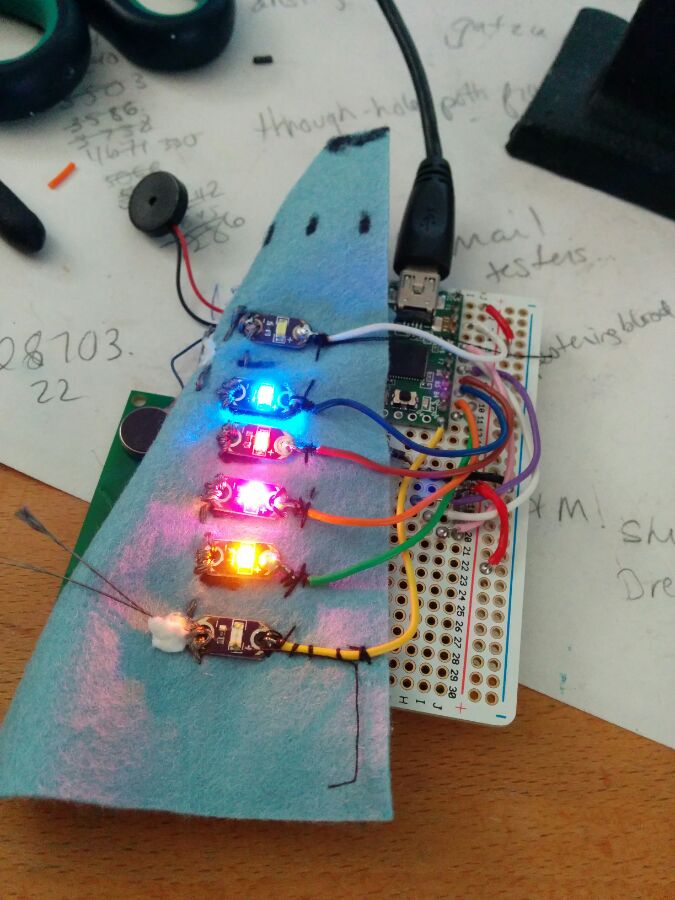

To investigate possibilities the study examines what is the current practice in retail, and what might be a possible solution using ST. It will go through a prototype stage as the device / program is being created, using Quick & Dirty user testing (where the aim is to get rapid, broad feedback on the design, a very simple form of ethnography) to get the initial prototype created. Then through additional user testing, there will be a retail prototype, the high fidelity version, created to put in store for testing in the environment with consumers.

Further sections contain critical discussions in the retail and technology areas. Following that will be detailed about the final testing to see if we have engagement and detail about how this could lead to further investigation.

Research Tools

To test the concept initially there will be a stage of iterative design, redesigning user interfaces on the basis of user testing can substantially improve usability (Nielsen 1993). The prototypes will go through a quick and dirty evaluation phase with different groups of people. All will be non-expert in this field but will have experience with commerce. They will be a variety of ages, and both male and female. These results will form a bulk of the process to get the correct final prototype for use in testing in a shop.

[1] Ferenczi, P., (2011) Mo’ Gadgets, Mo’ Problems, online at Mobiledia detailing the amounts of gadgets and time spent online or connected http://www.mobiledia.com/news/91317.html

[2] Examples of a doorbell that plays a portion of a melody, that reveals itself through the course of people coming to your door, a display of snippets from email messages that are recorded and displayed from a company, becoming a beautiful display of text portions and messages. “Critical Designer designs objects not to do what users want and value but to introduce both designers and users to new ways of looking at the world and the role that designed objects can play for them in it. This is often related to art-based projects as discussed by Hallnäs and Redström.” (Sengers, et al. 2005)

Figure 1 Usability will typically go up for each iteration (Nielsen 1993)

Using ethnographic observation[1] to observe behaviour in the retail environment, both with the device in situ and without. The observations will be compared with several main points, including dwell time, likelihood to engage with a device in store and interaction among consumers/consumers or consumers/staff. This will be followed up with post usage interviews with some of the consumers who engaged with the device as well as those that didn’t.

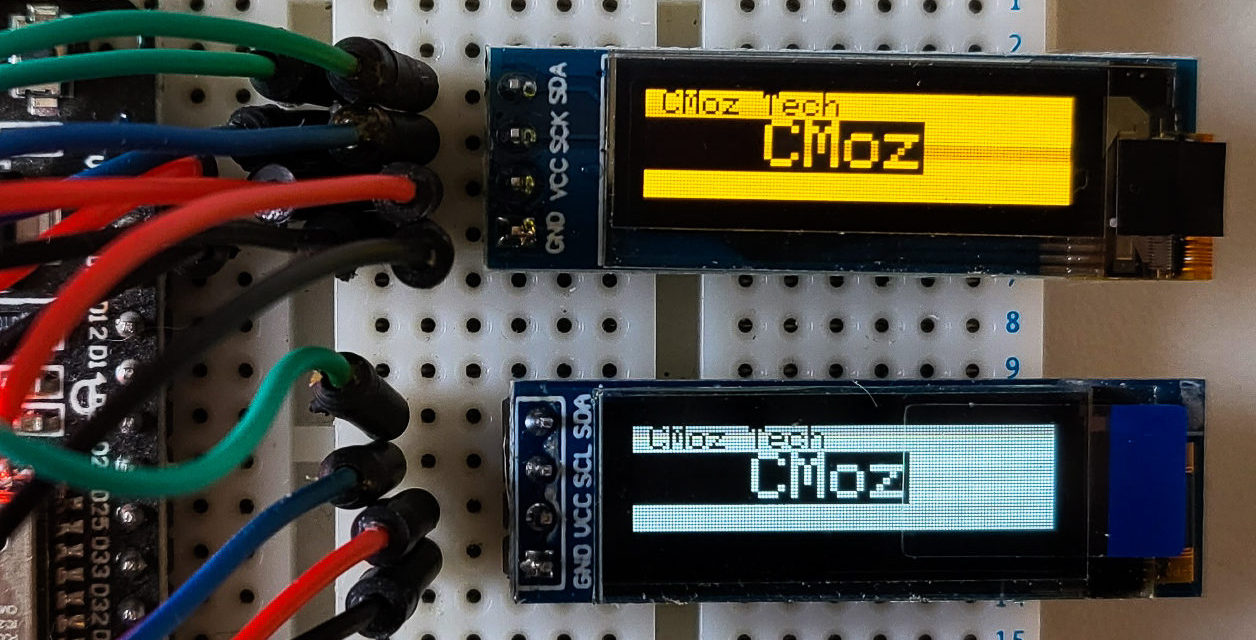

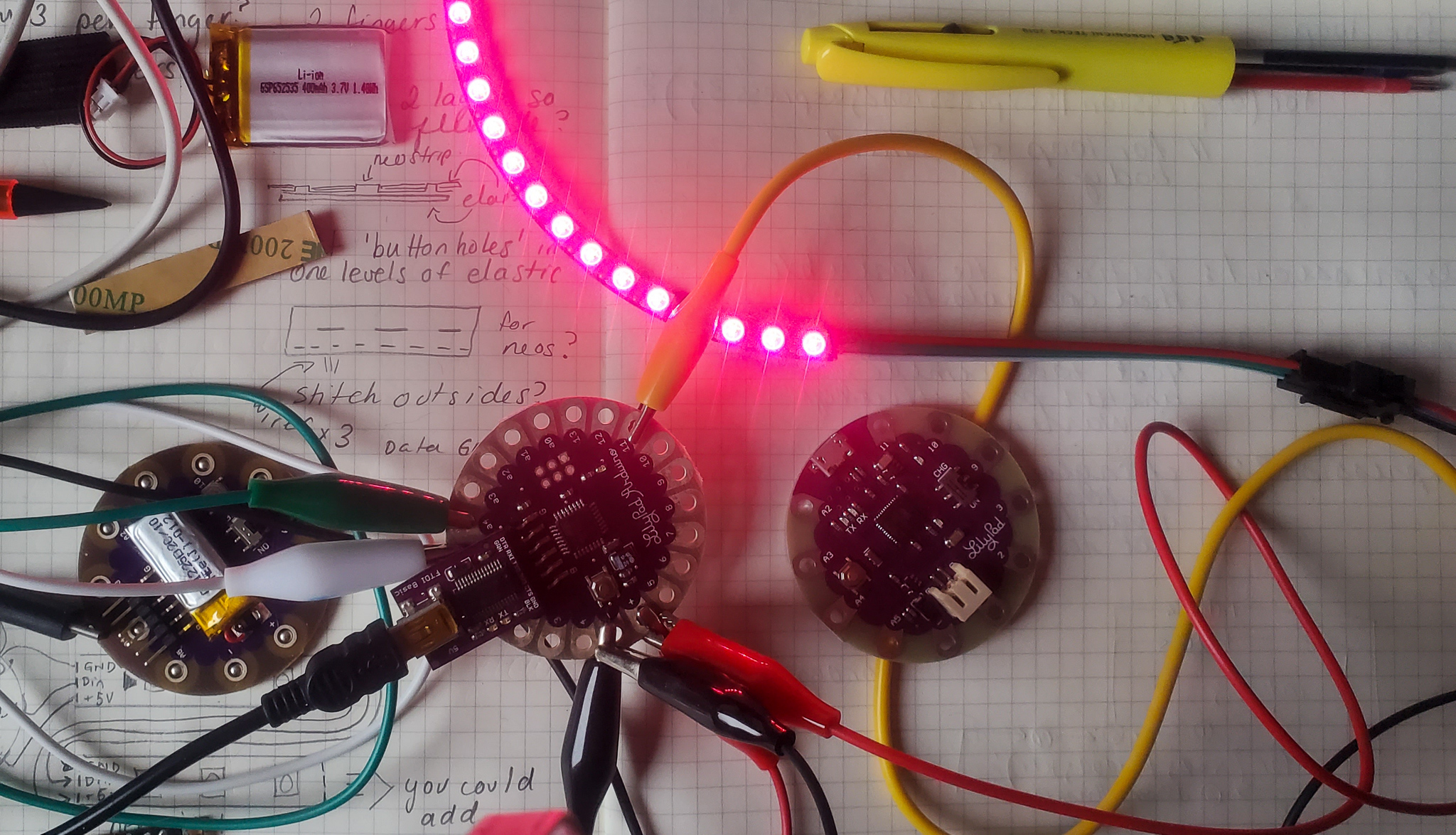

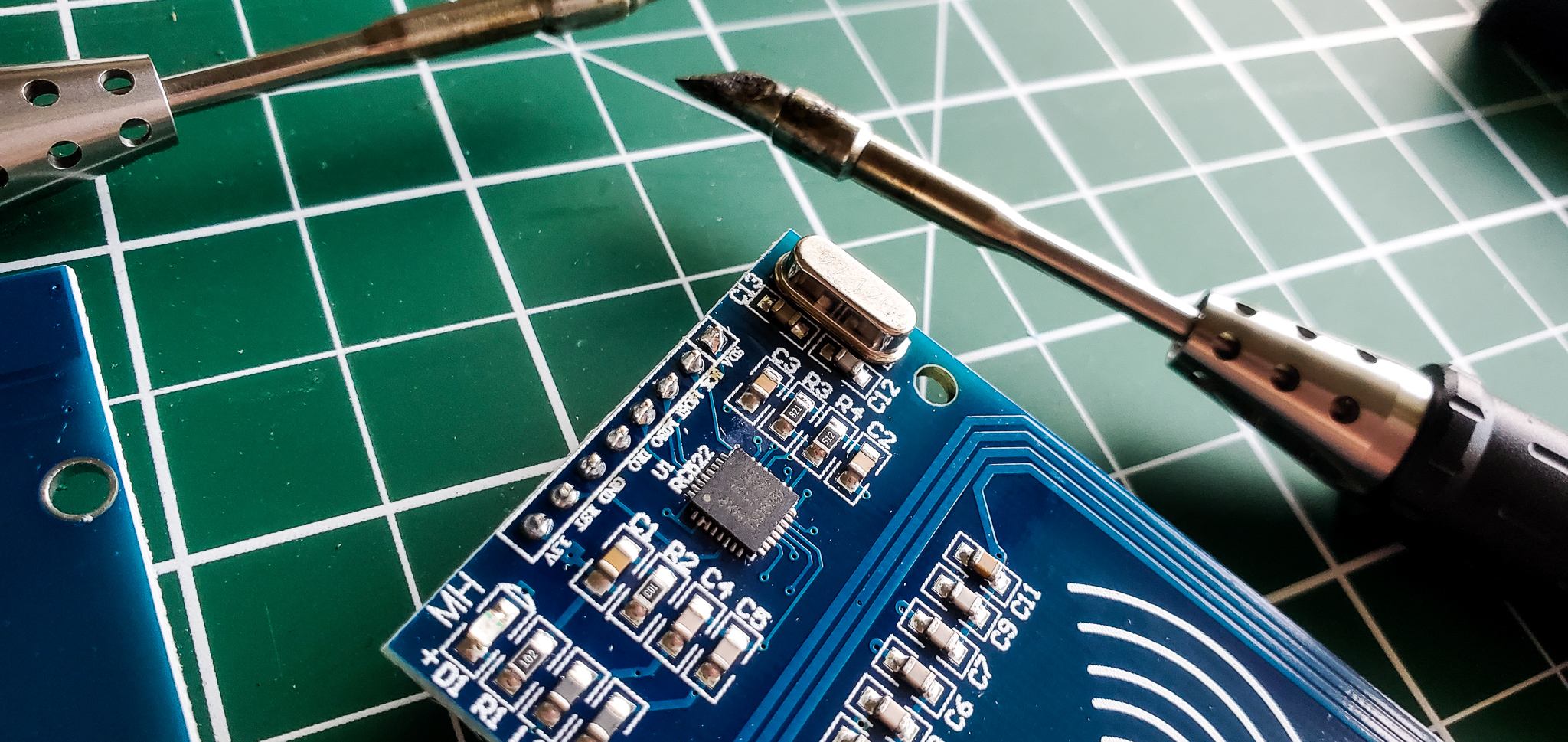

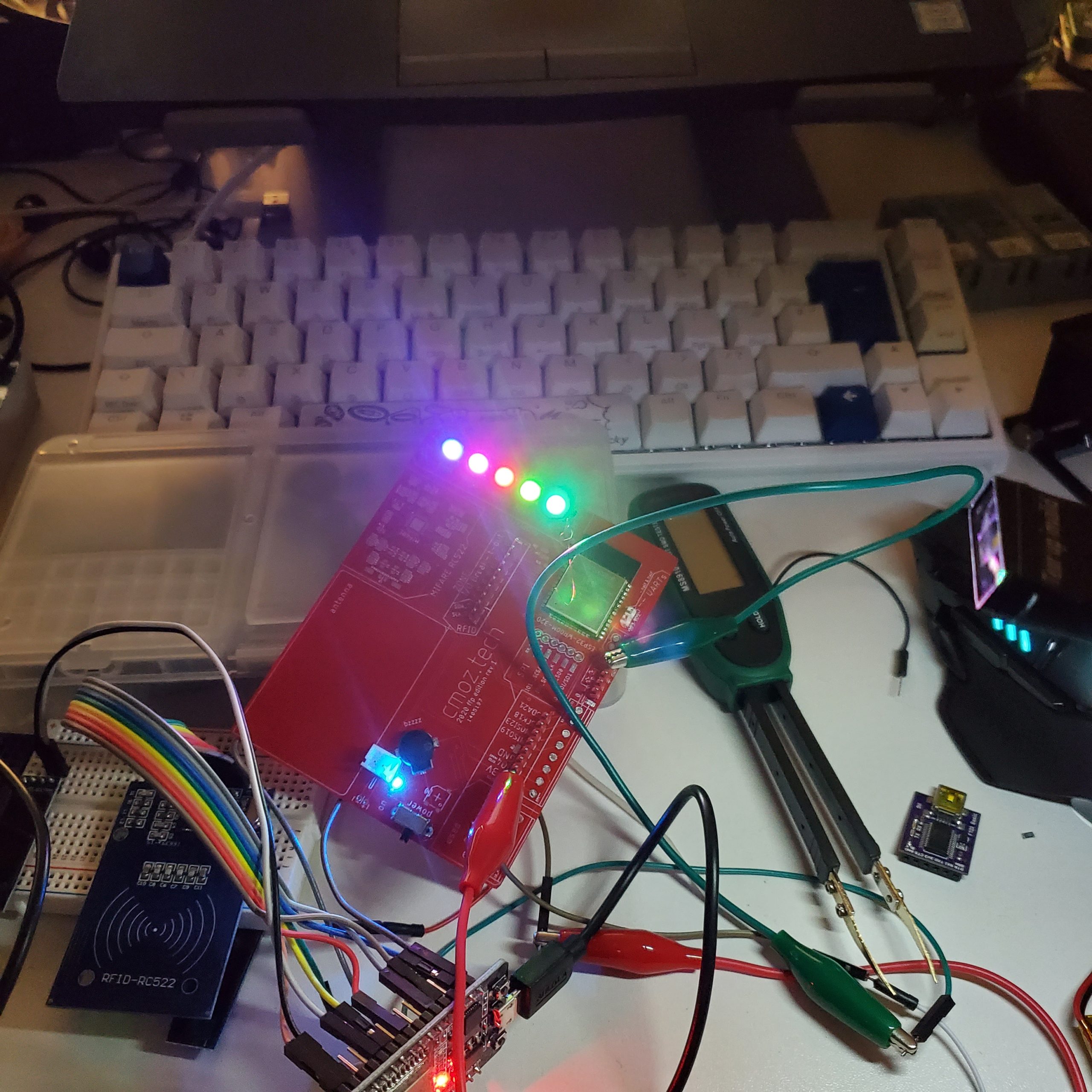

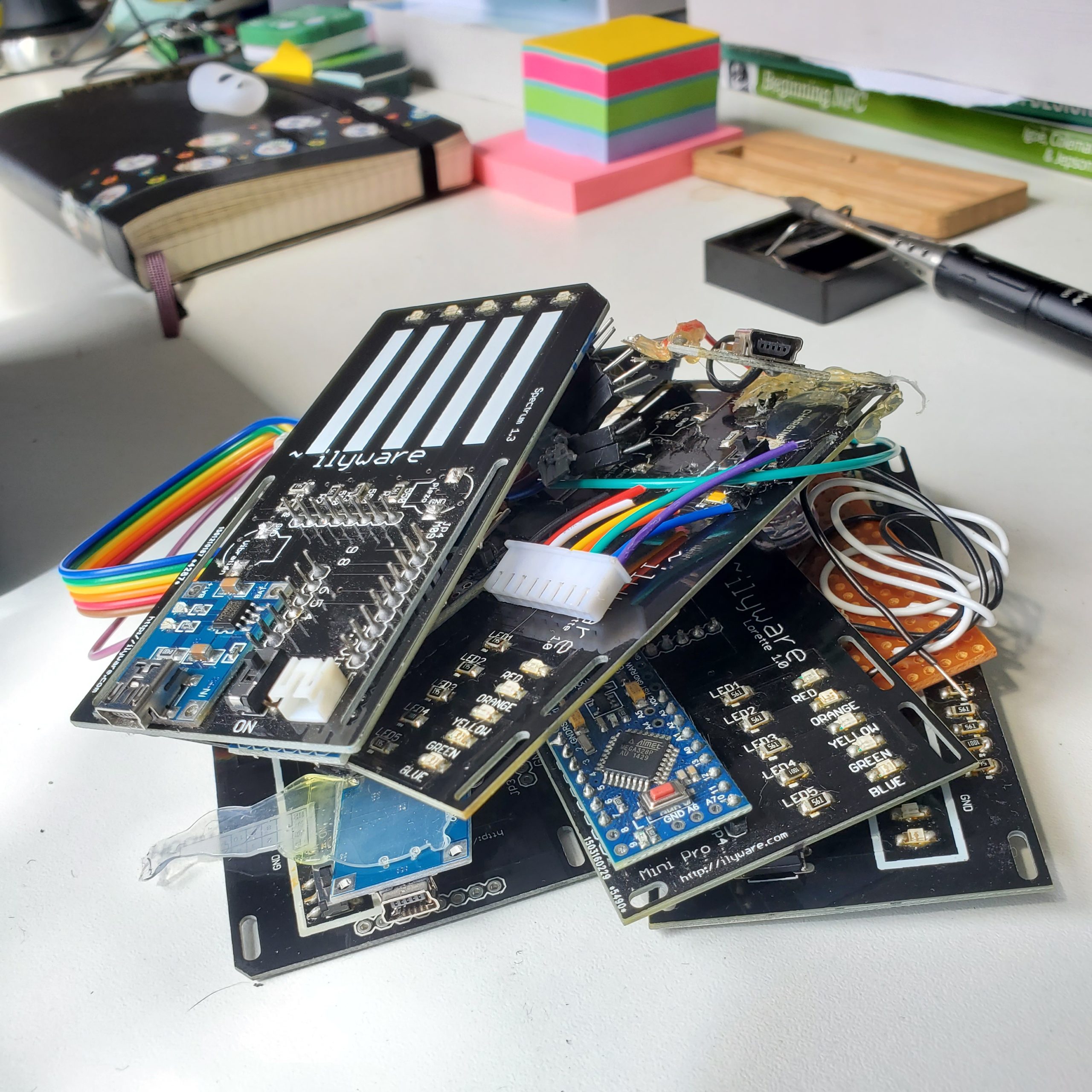

The alliterations of the device are noted and detailed in the Prototype (4.5) section, Iterations (4.4.1), which shows the changes made, the code altered and what the results were. Technical development is discussed in detail including problems that were encountered and the solutions implemented. There is also a critical discussion that follows.

[1] “The idea is that theories, hypotheses, insights, should emerge from the observations, so that they are grounded in observed experience.” Professor Andrew Hannan, available online http://www.edu.plymouth.ac.uk/resined/observation/obshome.htm#Ethnography.

Standard Approaches to Retail

“It’s not about technology” Matthews[1] said “it’s about the human interaction.”

One of the areas that the study leads to was a conversation with Mr. Tony Durham[2] from the P&G Brooklands Site, UK. Mr. Durham mentioned how consumer behaviour differs in different environments, noting how someone may behave in Tesco for example, and how that behaviour would differ in a different shop. He highlighted that a shopper in a large supermarket might be touching a lot of products, talking, maybe phoning and possibly distracted etc. He compared this with other types of shops / shoppers, and gave the example that this isn’t how someone in, for example, a shop like Tiffany’s will behave. There is a behaviour distinction and how consumers behave may differ according to their environment. So from this, we see the behaviour of ‘retail’ is environment specific. There is a clear distinction of space versus place. “Whereas space refers to the structural, geometrical qualities of a physical environment, a place is the notion that includes the dimensions of lived experience, interaction and use of a space by its inhabitants.” (Harrison and Dourish 1996) The place remains the same, this is a retail unit where products are sold to consumers, but if the space changes, if we are now assuming a certain kind of shop, then the behaviour is modified.

Is it possible to create the same atmosphere seen in more relaxed shopping areas, in to areas that are seen as more frantic?

Does the frantic busy behaviour we see in large retail shops echo the environment? Could this be related to ‘stuff-a-lanche’[3]? Stuff-a-lanche describes how there is too much ‘stuff’, too much media, too many things fighting for our attention. This notion is a part of the design statement, a need to reduce the clutter of ads in store for example. Many ads simply blend into the background visual noise in its environment and become little more than visual spam; “how to avoid your digital signage content becoming visual SPAM” was a focus at Consumer Engagement Technology World Show[4] in San Francisco. (The panel was led by Scott Matthews, managing partner / CEO for Learning Evolution and MG Digital.)

Traditional shop layout dictates that the shelves could be stacked as high as possible and full, with labels, and even as in the photo show, additional products hanging off the sides all the way along the middle.

After customer surveys conducted by Walmart, results showed they asked for more space and less clutter, changes are being made to current layouts to test if this is what customers actually want. In some retail superstores, the layout is being modified to give the consumer more space. (There is some controversy however if this is actually what the customer wants and perhaps they are viewing it as ‘less choice’ if there are fewer products out.)

Below is a traditional layout for a supermarket:

Figure 4 Traditional Supermarket layout.

An alternative layout currently being tested (fig 4). It shows the enhanced pharmacy/nutrition, technology and beauty areas, providing more space for the consumer and more chances to take their time to browse.

Figure 5 One superstore layout where there is an increase in space for areas such as Beauty, Technology and Pharmacy / Nutrition. Could these be the areas to target with ST?

These areas could be seen as a shop within a shop, and to entice the shoppers to spend more time in their stores and to choose a greater range of products.

People

In this instance, people are defined as the consumers as anticipated for whom this product would be most appropriate. Testing the Gillette angle (shaving tips) / Pampers angle (parenting advice?) or Beauty, the aim will differ according to the shoppers that are targeted. Figure 6 shows one area where Last Planet could be placed as this is targeted as a more relaxed area of the store.

Figure 6 One of the new display areas in a Supermarket. Creating a larger area for the consumer, moving away from the huge piled high shelves.

This new beauty area was considered, as well as a new parent/baby zone were considered for the initial testing of Last Planet, however after a discussion it was decided that it may be initially better to test it on the younger males due to the perceived use of technology in this age bracket and willingness to try new technology/products out. The proposed Slow Technology experience was displayed near men’s shaving products, so the target may be predominantly males over 18. Although this study focused ultimately on Gillette and in the men’s shelving area, but could easily be targeted adapted to Beauty section counters, or the baby aisle etc.

Consumer segmentation

This focuses on those segmentation groups found within the range of people looked at. How each consumer group itself has segments, and how this may alter the use of ST. We may see that there is a large portion of younger males that approach the technology due to a curiosity of the device itself. This study showed a bias with regards to the age ranges as there was a larger amount of younger males (under 40) that used Last Planet throughout the public testing. However, as it was a relatively small sample (41 people observed) further study could pursue existing data on consumer segmentation and purchase habits and practices especially in different retail environments and determine the most suitable environment for deployment of such technology.

One segmentation tool used is Atmospherics[5]. This is an interesting research area that examines retail environments. It looks at how all areas of the environment, and how the senses are stimulated, will affect the consumer groups. Although there is not an extensive body of research done in this area, the studies that have been conducted all show a similar conclusion, that there can be several responses to the environment (Bitner 1992), and noted that responses such as cognitively, emotionally, and physiologically to it.

It is also documented that different personality traits could have different reactions (Meharabian and Russell 1974; Russell and Snodgrass 1991). It is important to note that Action Oriented Shoppers who have defined goals before they shop are less likely thought to be influenced by displays (Babin and Darden 1995), it is important because, during the tests, it was observed that the people who grabbed a basket at the start of the shop were less likely to physically touch the device, they had clear intent with their purchases.

In order for ST to be optimal in its usage to enhance the environment, further studies into the retail environment may need to be done to be sure the environments match the personalities targeted.

[symple_heading type=”h2″ title=”Purchase Habits” margin_top=”20px;” margin_bottom=”20px” text_align=”left”]

Slow technology can be used to enhance an experience so they have less perceived rush and have reflection time, a talking point, useful yet not ‘pushy’.

There are behaviours observed and noted, (Meharabian and Russell 1974) detail Approach-Avoidance Behaviour which is “a behavioural reaction to a retail atmosphere, which is somewhat, related to sales. Approach behaviours are manifested in positive responses to an environment including a desire to explore it and willingness to stay in it for relatively long periods of time. In contrast, avoidance behaviours are associated with negative reactions to an environment including a desire to leave and not return.” (Turley and Chebat 2002)

Meharabian and Russell’s work was examined further into retail environments to suggest that “the effects of a store’s atmosphere are manifested in emotional states which are difficult to express verbally, are transient and may not always be fully recalled when questioned later, and are likely to influence in-store behaviours more than store choice decisions.” (Donovan and Rossiter 1982)

The purchase habits look to be wrapped up in environmental factors and the behaviours will make a difference to the likelihood of purchases or not. The willingness to explore the shop, may lead to a more positive experience, in turn, increases the dwell time and their purchases.

PAD dimensions (Turley and Chebat 2002) referred to in literature describe three emotional states that mediate this approach-avoidance behaviour, pleasure, arousal and dominance, which was seen as a tool (Donovan and Rossiter1982) to have the ability to influence shopping behaviour. Although studies support that the atmosphere created does affect the consumer, their desire to browse[6] or make purchases, impulse purchases, based on the environment, there is disagreement over whether it is pleasure, arousal or dominance that is influencing behaviour (Turley and Milliman 2000).

Standard Approaches for Technology

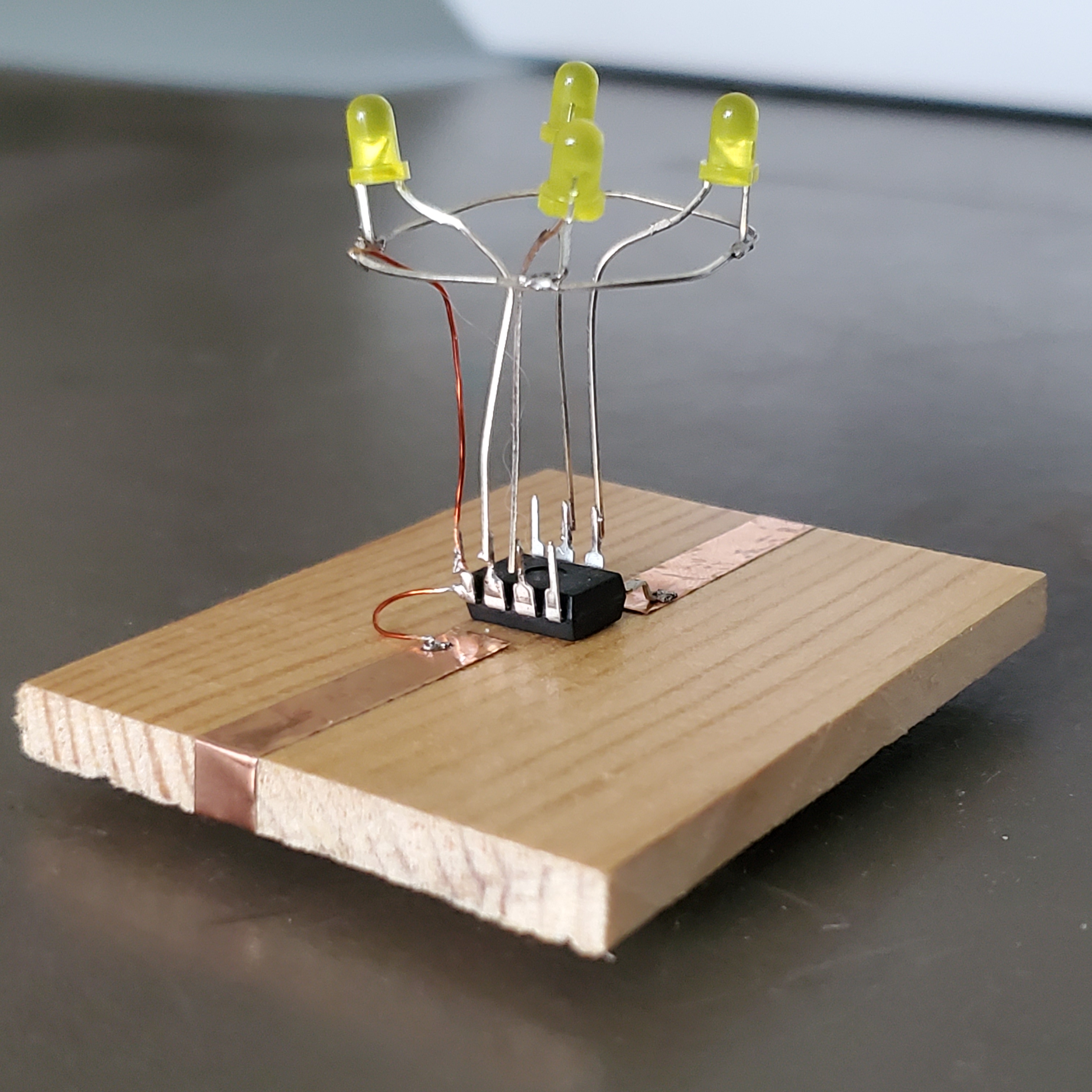

This section examines the interaction that is currently offered in stores and what are the user reactions to it. This could be from a simple flashing LED[7] to the shop floor TESLA monitors to design your own car. What is the interaction, why does this matter, what does it tell us and (why) do I want to replicate that experience?

One proposal considered was a wall that was interactive and representative of the environment. Although this is still an area for future exploration, after completing the literature review, the wall wasn’t a feasible as a first prototype solution. This section explains the items looked at for consideration in implementing ST into a retail environment.

[1] http://www.digitalsignagetoday.com/article/192870/How-to-keep-digital-signage-content-from-becoming-visual-spam

[2] Mr. Tony Durham has been working in retail for over 30 years and travels across Europe advising many brands & corporations about their retail strategy.

[3] Brooker, Charlie, There’s too much stuff. We live in a stuff-a-lanche. It’s time for a cultural diet. The Guardian. October 2009. Article available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/oct/05/charlie-brooker-cultural-diet [Accessed June 2012].

[4] Information available at http://cetworld.com/

[5] The term used to describe the discipline of designing commercial spaces, it is the “conscious designing of space to create certain effects in buyers” or more precise, “the effort to design buying environments to produce specific emotional effects in the buyer that enhance purchase probability”. Kotler, P. (1973). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing, 49(4), 48-64.

[6] Described as “staying in a store and exploring what it has to offer”. (Turley and Chebat 2002)

[7] Tony Durham discussed that one instance saw a store place a single flashing LED above a coupon distributing machine, in mid aisle, and noted that every single person was drawn or had looked at it. He commented that it’s human behaviour to notice something, which may signal danger, and we are drawn to it whether we want to be or not.

Examples of Technology in Retail

Current technology being used in this area, include visuals from an Ogilvy Retail Lab Day[1] attended in London (May 2012) about new and interesting ways to bring marketing strategies to retail, including new technologies with displays, projections (one projection was on a freezer door displaying ice cream, with a combined stagnant image pasted on to the lower half of the door, and a moving projection about the ice cream overlaid, this was very effective and everyone was drawn to it), iPads / codes etc different campaigns employed with technology.

Due to the market saturation[2] of the iPad it is now accepted that it is no longer seen as a unique item as when it was first introduced in 2010.

Figure 9 shows a number of iPads that have been sold up to Q3 2012.

The iPad and its ability to attract people was an area for initial concern, but due to the saturation of the iPad, it wasn’t an area that needed testing, e.g. is a consumer only interested in looking at the iPad from the wow factor of having an iPad there. They are now a lot more common, making appearances in supermarkets, shops, car dealerships and so on. Other screens that we see in retail environments are mounted high and display advertisements for the products on the shelves. As in this Maybelline display in Boots.

Figure 10 Maybelline using a display unit, which is passive, only displaying advertising.

This display only offers the consumer the options of viewing it, and there is no interaction. In addition, due to its high placement it almost goes un noticed because the shoppers are busy looking at the products below. Observations in this shop happened over the period of over an hour and during that time, although many shoppers were in the area, had looked at the products, had stayed by the display – non-engaged or watched the video.

Another display noted in the retail environment of a car dealership was this touch screen. Similar to the Maybelline display, it had very few interested people engaging. The car dealership one did encourage touching and was in a more visible less cluttered place but under observation, it was only the children waiting that touched it. The content is a typical ad style, with information heavy pages about the product they are trying to sell.

Figure 11 Interactive display on a sales desk in a car showroom.

Ubiquitous Computing

The idea of ubiquitous computing was introduced in 1991, by Weiser, and computers at that time were mostly desktop systems, so ubiquitous was understood to mean to include processes in everyday objects and actions. The idea was that it would be making computers invisible (Weiser 1993), and in practice, this means they need to be made transportable, which the iPad absolutely is. Although initially, this idea did relate to hardware, the notion was made that this should also take into account the software interface and that, “that the challenge would be to recreate the relationship between people and computers, hence looking at the action of the user.” We see that Dourish refers to this idea, and takes it further by the concept of Embodied Interaction, which looks at the relationship of tangible interfaces and social computing from the perspective of interaction.

One part of this concept describes one area for investigation is creating an environment for activity of the computer, to interact directly with the physical artifacts as opposed to using traditional interfaces in this field e.g. the mouse, he explains, “Mice provide only simple information about movement in two dimensions, while in the everyday world we can manipulate many objects at once, using both hands and three dimensions to arrange the environment for our purposes and the activities at hand.” (Dourish 2001) This encompasses the use of the iPad perfectly, as it is up to the user to involve them directly with the interface.

Slow Technology as a Solution

(Jason Goldberg 2012), “the majority of deployments are not delivering paid ads, the video based displays are used to enhance shopping experiences” (Time Business).

Can a calming and engaging in-store experience which integrates passive or active user interaction act as a new medium to capture a consumers attention, ultimately leading to the potential of driving brand awareness/facilitate product placement and influence consumer behaviour and engagement in the retail experience? How can ST be used to facilitate this?

[1] Information available online at http://londonlab.ogilvyeurope.com

[2] See Fig.3 for an indication that the iPad is now accepted within society due to the number of years it’s been available and volume of sales generated. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IPad#First_generation

Slow Technology

In the search to create an engaging, calming in store experience, Slow Technology was researched as an area for development. ST projects have similar aims of trying to engage / calm, but in a different environment. The opposing ideals of retail and calm could have potential, and it is in this study that mixing the two for initial study and to see if Slow Technology can be used effectively – e.g. increase dwell time, encourage interaction etc, in a retail environment.

Figure 12 An example of Slow Technology – these timers set to limit the amount of time we spend checking / updating our Facebook & Twitter accounts.

This document looks at an initial proposal and the points raised within it, the break down of these points with the current investigations / information taking place as well as further research that could be undertaken will be covered. The guidelines for slow technology should be outlined as a starting point, as clarified in the paper by Hallnäs and Redström 2001:

- focus on the slowness of appearance (materialization, manifestation) and presence – the slow materialization and design process of form (F)

- focus on aesthetics of material and use simple basic tools of modern technology – the clear and simple design presence of material (M).

The design should give time for reflection through its slow form-presence and invite us to reflect through its clear, distinct and simple material-expression. It is a combination of simplicity in the material with a subtle complexity in form focusing on time as a basic element of the composition. Technology should bring forth the material, not hide it. (Hallnäs and Redström 2001)

Ludic Element & Engagement for the user

“Presenting the strange or the unfamiliar may alienate, confuse, or simply not interest people. So this must be done in a way that gives footholds for interpretation. We refer to this as providing digital scaffolding for bridging from the familiar to the unfamiliar. One method is to use playfulness in a way that makes people feel included.” (Sengers, et al. 2005) The element of playfulness will be important to be able to encourage consumers to return and the overall effect of them feeling included is desirable.

In addition to the ST focus areas, in order to satisfy engagement, rules of play / fun elements need to be considered. For many, shopping is an experience, which should be a “fun” activity, or at least has the potential to be. Consumers seek excitement and arousal from the environment of a retail store and spend more money in these types of environments (Babin and Darden 1995).

There are certain elements to change or enhance the atmosphere, which can be used to entertain consumers. These include music, in-store televisions, interactive displays and kiosks, live performances by a variety of artists, product use demonstrations and seminars or displays with products out for the customer to touch, feel and see exactly what they are getting. Tony Durham explained that in one shop, there was a display of toothbrushes, that were displayed in a way so that they were not in packaging and consumers could touch and examine closer the actual toothbrushes. Not only did it increase sales of those particular toothbrushes on display, but also the entire category range of toothbrushes saw an increase in sales.

Most of these attempts at entertaining customers recognize that keeping shoppers in stores longer is likely to result in increased browsing behaviour, which in turn is likely to cause increased impulse purchasing (Beatty and Ferrell 1998). Additionally, if you can keep them in your store for longer, chances are that it may reduce the amount of time they spend in the competitors’ shops (Turley and Chebat 2002).

Figure 13 This Social Bomb sounds pretty dangerous- limiting your connection in a social atmosphere, take control of weddings or movie theatres by switching off the mobile phones in the area.

Using playful elements in Last Planet how / why / to what effect / Rules of play… (Salen and Zimmermen 2003) Last Planet is one solution to implement ST, which aims to demonstrate if it is able to capture the attention of shoppers and encourage their interaction and reflection more than typically seen in that environment. The environment can be changed, through the use of atmospheric variables such as colours, layout, music, flooring, lighting and merchandise arrangements creates a package surrounding the merchandise, which can create a unique shopping experience.

Example uses of Slow Technology

Some of the ST projects that surfaced at ‘Slow Tech’[1] recently are dealing with the obsession of social media, and our need to update and consume media. An egg timer-styled device, was designed by Eccles who says the intention was to use iconic forms throughout the project to help illustrate the point, Eccles and Mehin envisioned “the Social Timer as a tabletop object that would disable a particular type of communication for a shorter amount of time, such as a family dinner.” The timers also have Facebook and Twitter symbols on the top like salt and pepper shakers, as a subtle reminder of their purpose (fig.12).

Figure 14 Serious social networking! The Social Sentinel shows employees when they can get online to be social as it limits time and access to social networks.

Another example is the Social Bomb (fig. 13) that forces us to take a break, as it cuts off all forms of technology. It is for social places such as weddings or similar group settings where it encourages politeness, by disabling the devices. One last example from this exhibition is the Social Sentinel (fig. 14), which is set up then mounted on the ceiling in a room. It shows you when certain types of social activities are permitted and activated before getting shut off, presumably during work hours.

Figure 15 Photobox, the technology designed to take years to be ‘used’.

An alternative example of slow technology that doesn’t focus on your social usage / time allocation as such is Photobox[2], which has access to your Flickr account, and every so often, it prints one of the photos. When you go to open the box, you may see one or several photos. Its intention is to be used over many years.

“The behaviour Photobox enacts is to search its owner’s Flickr collection, randomly select a single image, and then print this image within the box where it will wait to be discovered.” (Odom et al 2012)

[1] An exhibition in London, London Design Week group show, September 2011, http://prote.in/feed/2011/09/slow-tech

[2] Odom, W., Selby, M., Sellen, A., Kirk, D., Banks, R., Regan, T., Photobox: On the Design of a Slow Technology, Presented at DIS 2012.

References

Ascharya, K., Slow Tech: An Idea Whose Time Has Come, (2012) Available http://www.mobiledia.com/news/156804.html

Baker, Julie, Levy, Michael, and Grewal, Dhruv (1992), “An Experimental Approach to making Retail Store Environmental Decisions,” Journal of Retailing, 68(4), pp. 445-460

Bawa, Kapil, Landwehr, Jane T. and Krishna, Aradhna (1989), “Consumer Response to Retailers’ Marketing Environments: An Analysis of Coffee Purchase Data,” Journal of Retailing, 65(Winter), pp. 471-495

Bell, G., Blythe, M., and Sengers, P. Making by making strange: Defamiliarization and the design of domestic technology. ACM TOCHI 12(2) June 2005, 149-173.

Bellizzi, Joseph A., Crowley, Ayn E. and Hasty, Ronald W. (1983), “The Effects of Colour in Store Design, “ Journal of Retailing, 59(Spring), pp. 21- 45

Bitner, Mary Jo (1992), “Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees,” Journal of Marketing, 56(April), pp. 57-71

Boehner, K., Thom-Santelli, J., Zoss, A., Gay, G., Hall, J., and Barrett, T. Imprints of Place: Creative Expressions of the Museum Experience. Extended Abstracts of CHI 2005, ACM Press, 2005.

Brooker, C., There’s too much stuff. We live in a stuff-a-lanche. It’s time for a cultural diet. The Guardian. October 2009. Article available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/oct/05/charlie-brooker-cultural-diet [Accessed June 2012].

Cairns, P., Cox, L. (2008). Research Methods for Human-Computer Interaction, Cambridge University Press

Chen, X., Shao, F., Barnes, C., Childs, T., & Henson, B. (2009). Exploring relationships between touch perception and surface physical properties. International Journal of Design, 3(2), 67-77.

Chevalier, Michel (1975), “Increase in Sales Due to In-Store Display,” Journal of Marketing Research, 12(November), pp. 426-431

Djajadiningrat, T., Kyffin, S., Overbeeke, K., Wensveen, S., Freedom of Fun, Freedom of Interaction, Interactions, September/October, 2004. (pp 59-61).

Donovan, Robert J., Rossiter, John R., Marcoolyn, Gilian and Nesdale, Andrew (1994), “Store Atmosphere and Purchasing Behaviour,” Journal of Retailing, 70(3), pp. 283-294

Fallman, D. (2003). Design-oriented human-computer interaction. Proceedings of the conference on Human factors in computing systems – CHI’03, (5), 225. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. doi:10.1145/642651.642652

Ferenczi, P., (2011) Mo’ Gadgets, Mo’ Problems, online at Mobiledia detailing the amounts of gadgets and time spent online or connected http://www.mobiledia.com/news/91317.html

Garfinkel, H., Rawls, A., Ethnomethodology’s Program. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0742516423. Page 6.

Gaver, W. (1991). Technology affordances. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems: Reaching through technology. doi:10.1145/108844.108856

Grossbart, Sanford L., Mittelstaedt, Robert A., Curtis, William W. and Rogers, Robert D. (1975), “Environmental Sensitivity and Shopping Behaviour,” Journal of Business Research, 3(4), pp. 281-294

Hallnäs, L., Redström, J., Slow Technology – Designing for Reflection, Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5(3) 2001.

Hallnäs, L., & Redström, J. (2002, June). From use to presence: on the expressions and aesthetics of everyday computational things. Journal ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) , 9 (2) , 106-124. NY: ACM New York.

Harrison, S. and Dourish, P. Re-place-ing space: the roles of place and space in collaborative systems. Proc. of CSCW’96. ACM 1996. 67-76

Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Beacon Press, Boston, MA, USA 1950.

Kotler, Phillip (1973), “Atmospherics as a Marketing Tool,” Journal of Retailing, 49(Winter), pp. 48-64

Leshed, G., Sengers, P. 2011. “I lie to myself that I have freedom in my own schedule”: productivity tools and experiences of busyness. Proc. of CHI ’11.

McKinnon, Gary F., Kelly, J. Patrick and Robison, E. Doyle (1981), “Sales Effects of Point-of-Purchase In-store Signing,” Journal of Retailing, 57(Summer), pp. 49-63

Martineau, Pierre (1958), “The Personality of the Retail Store,” Harvard Business Review, 36(January-February), pp. 47-55

Meharabian, Albert and Russell, James A. (1974), An Approach to Environmental Psychology, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press

Nielsen, J., Iterative User Interface Design, Originally published in IEEE Computer Vol. 26, No. 11 (November 1993), pp. 32-41.

Norman, D. (1998), The Design of Everyday Things. Massachusetts, USA: The MIT Press.

Odom, W., Selby, M., Sellen, A., Kirk, D., Banks, R., Regan, T., Photobox: On the Design of a Slow Technology, In the Proceedings of DIS 2012, June 11-15, 2012, Newcastle.

Price, A., (2009), Slow-Tech: Manifesto for an Over-wound World. Atlantic Books.

Reyner, M., (2011) Slow Tech, Available online http://prote.in/feed/2011/09/slow-tech

Russell, James A. and Snodgrass, Jaclyn (1991), “Emotion and the Environment,” Pp 245-280 in Handbook of Environmental Psychology, Stokols Daniel, and Altman Irwin, (Eds.), Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company

Salen, K., and Zimmerman, E. Rules of Play. MIT Press, Boston, MA, USA, 2003

Shneiderman, B., Designing the User Interface, Fourth edition, Addison-Wesley, 2003

Sengers, P., Boehner, K., David, S., Kaye, J., Reflective Design, Proceedings of the 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing: Between Sense and Sensibility, 2005.

Shu-Luan Kao, (n.d.). The Effect of Retail Store Display Atmosphere on Consumer’s Attention, Perceived Value, and Purchase Intention _ A Case of Grid Shop in Taiwan.

Subramanian S, Subramanian A (1995). “Reference group influence on innovation adoption behaviour: incorporating comparative and normative referents,” European Advances in Consumer Research, 2, 14-18.

Slow Technology: Critical Reflection and Future Directions, Available Online http://www.willodom.com/slowtechnology/

Turley, L.W., Chebat, J. (2002) Linking Retail Strategy, Atmospheric Design and Shopping Behaviour, Journal of Marketing Management, 18:1-2, 125-144

Turley, L.W. and Milliman, Ronald E. (2000), “Atmospheric Effects on Shopping Behaviour: A Review of the Experimental Evidence,” Journal of Business Research, 49(2) pp. 193-211

Turley, L.W. (2000), “How ‘Atmospherics’ can Differentiate Retail Outlets,”European Business Forum, 4 (Winter), pp. 49-52

Wakefield, Kirk and Baker, Julie (1998), “Excitement at the Mall: Determinants and Effects on Shopping Response,” Journal of Retailing, 74(4), pp. 515-539

Wensveen, S. A. G., Djajadiningrat, J. P., & Overbeeke, C. J. (in press). Interaction frogger: A design framework to couple action and function. In Proceedings of the DIS2004. Cambridge, MA.

Weiser, M. (1999). The computer for the 21st century. ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review – Special issue dedicated to Mark Weiser , 3 (3), 3 – 11.

Wixon, D., (2003) “Evaluating Usability Methods: Why the current Literature fails the practitioner”, Interactions (July/August).

Woodside, Arch G. and Waddle, Gerald L. (1975), Sales Effects of In-Store Advertising,” Journal of Advertising Research, pp. 29-33